For noen år siden, fordi jeg begynte å lese mer om LHBT+ både i bøker og på nett, oppdaget jeg at «aseksuell» en ting. Den merkelappen tror jeg ikke fantes når jeg vokste opp på 80- og 90-tallet. Om den gjorde var den i alle fall ikke noe folk flest hadde hørt om. Mye av det som definerer aseksualitet var veldig gjenkjennelig, og etter å ha satt meg mer inn i det har jeg vel landet på at jeg er både demiseksuell og demiromantisk (to merkelapper som begge faller inn under Ace-paraplyen). Lykkelig gift som jeg er er det likevel en slags lettelse å få plassert meg selv i en sammenheng som gir mening til alt jeg har tenkt og følt (eller kanskje helst IKKE følt) om romantisk kjærlighet og sex i mine noen-og-førti år på jorda. Å putte denne boka i handlekurven på en av mine shopping-runder hos Waterstones’ nettbutikk var derfor en no-brainer.

For noen år siden, fordi jeg begynte å lese mer om LHBT+ både i bøker og på nett, oppdaget jeg at «aseksuell» en ting. Den merkelappen tror jeg ikke fantes når jeg vokste opp på 80- og 90-tallet. Om den gjorde var den i alle fall ikke noe folk flest hadde hørt om. Mye av det som definerer aseksualitet var veldig gjenkjennelig, og etter å ha satt meg mer inn i det har jeg vel landet på at jeg er både demiseksuell og demiromantisk (to merkelapper som begge faller inn under Ace-paraplyen). Lykkelig gift som jeg er er det likevel en slags lettelse å få plassert meg selv i en sammenheng som gir mening til alt jeg har tenkt og følt (eller kanskje helst IKKE følt) om romantisk kjærlighet og sex i mine noen-og-førti år på jorda. Å putte denne boka i handlekurven på en av mine shopping-runder hos Waterstones’ nettbutikk var derfor en no-brainer.

I How to be Ace får vi følge Rebecca fra tidlige tenår, når alle andre plutselig ble kjempeinteressert i kjærester og sex, til nåtid, der hen er anslagsvis rundt 30 og etablert som illustratør. Både forvirringen rundt seksualitet og psykiske problemer (hen har OCD og angst, og i følge baksideteksten er hen autist også) skildres ærlig og åpenhjertig, og selvutleverende. Innimellom presenteres faktabokser som gir leseren bakgrunn for noen av begrepene som lanseres. Tegnestilen er sjarmerende og er i aller høyeste grad med på å fortelle historien. Er begrepet aseksuell nytt for deg er dette en bra intro.

For meg ble boka mindre bra enn den kanskje kunne ha vært fordi jeg ikke klarte å la være å sammenligne den med Alice Osemans Loveless (som også handler om aseksualitet) som jeg leste før jul (og ikke har skrevet om ennå, fy meg). Gjenkjennelsesfaktoren i Loveless var for meg langt større, og leseopplevelsen min av begge bøkene er farget av det. How to be Ace handler som sagt også mye om psykisk helse, og det er ikke negativt i seg selv, men jeg hadde forventet en slags grafisk variant av Loveless, og det var ikke det jeg fikk, og så ble jeg kanskje urimelig skuffet. Det blir interessant å gjenlese How to be Ace om et år eller noe, og se om opplevelsen blir annerledes når jeg er forberedt på tematikken. Den skal få forbli i hjemmebiblioteket, i alle fall, så får jeg muligens diskutere med tenåringen hvem sin hylle den skal bo på.

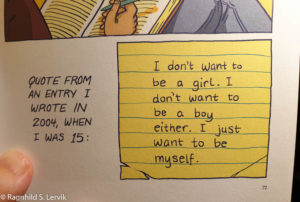

Gender Queer is a graphic memoir about growing up not feeling at home with the body you are given, and especially not with the expectations that come with that body. Maia Kobabe grew up (mostly, e was born in 1989, as far as I can calculate) before the internet became a total immersion experience, and hence at a time when finding «other people like me» was a much more difficult process. This memoir tells the story of eir process from being perceived as a «tomboy» when e was little enough that that was an option, hitting puberty and struggling with that on a whole other level than eir friends and slowly discovering that not only are there more options sexuality-wise than boy+girl, but that «boy» and «girl» in themselves are identites that can be questioned.

Gender Queer is a graphic memoir about growing up not feeling at home with the body you are given, and especially not with the expectations that come with that body. Maia Kobabe grew up (mostly, e was born in 1989, as far as I can calculate) before the internet became a total immersion experience, and hence at a time when finding «other people like me» was a much more difficult process. This memoir tells the story of eir process from being perceived as a «tomboy» when e was little enough that that was an option, hitting puberty and struggling with that on a whole other level than eir friends and slowly discovering that not only are there more options sexuality-wise than boy+girl, but that «boy» and «girl» in themselves are identites that can be questioned.