Mutton is a free-standing sequel to Comfort and Joy (which I loved) though I only realised this once I started reading, as the publishers have completely neglected to include this information on the cover. This is a shame, because, although you could quite definitely read Mutton all on its own, it does contain Comfort and Joy spoilers, so if you want to read both you should definitely read them in the correct order.

Mutton is a free-standing sequel to Comfort and Joy (which I loved) though I only realised this once I started reading, as the publishers have completely neglected to include this information on the cover. This is a shame, because, although you could quite definitely read Mutton all on its own, it does contain Comfort and Joy spoilers, so if you want to read both you should definitely read them in the correct order.

Clara is still my BFF, or something like that. I like her a lot. The two of us have differing views on things like shoes (I’m more interested in comfort than looks) and makeup (I can hardly ever be bothered), but so do a lot of my real life friends. What Clara does have in common with me (I think) is what the cover calls «a healthy sense of what matters in life». But then Clara’s old friend Gaby moves in. Gaby is older than Clara but looks substantially younger. Because, of course, she has had «things done». And Clara, who has just discovered a frown taking root on her forehead, starts wondering whether, perhaps, she should get a few things done herself.

I’ve never been the sort of person who worried too much about how I look (hence the lack of interest in shoes and makeup), but I do see how a nip here, a tuck there and a little shot of Botox may seem quite tempting to people (we’re talking the subtle(ish), small alterations here, not full-on duck lips and scary expressionless faces). And it’s all very well to tell people to «grow old gracefully» as long as most actresses don’t look a day over thirty (even the ones that are supposed to be old) and women get laughed at for not dressing their age (as if, magically, at say, forty, we should stop liking to dress up and start preferring shapeless beige and navy dresses). And if you’re single, as both Clara and Gaby are, and would rather like to have sex with someone vaguely attractive (to you, definitions differ, obviously) occasionally, then living up to what society tells you is an attractive woman will of course seem massively more important.

So Clara worries a bit, but on the whole her outlook is that it is what it is and if you have to forego pasta forever in order to live up to the ideal, then perhaps it’s the ideal that’s wrong, rather than the pasta. But having Gaby in the house is unsettling, however, not all is hunky-dory with Gaby either:

For the first time since she re-entered my life, I feel properly sorry for Gaby, beautiful, gorgeous Gaby, pretendy Gaby, who has made herself a captive of her looks, who can never stop, who is never going to say, ‘Sod it, I’m nearly fifty, I think I’ll skip the daily punishment and the starvation regime and just do what I like. And if my arms sag a bit, then so what? I’ve had a good innings and it isn’t the end of the world.’ Instead here she is, snaffling down the Class As and trying to keep up with people she could realistically have given birth to. Kate would say it’s undignified, and at this very moment I’m inclined to agree.

(p. 82) They rattle along, and learn bits and pieces on the way, helped along by some of Clara’s other friends. At the same time, things are going on with Clara’s son Jack and his girlfriend Sky. Sky’s father is a successful fantasy writer, in the middle of writer’s block over his seventh novel, and is sent by his publishers in isolation to the outer Hebrides in the hope that this might help, so Sky is also a temporary lodger i Clara’s house. It turns out that Gaby is a complete fangirl when it comes to Sky’s dad’s books, and that provides both entertainment (being a bit of a fangirl myself, I chuckle over Gaby and Sky and their conversations filled with in-jokes and unintelligble gibberish – to an outsider like Clara) and plot twists.

The main focus of Mutton, though, is looks, whether to «fix» them and how to live with them. As such, I found Mutton less engaging than Comfort and Joy, simply because looks interest me far less than divorce (or Christmas). And some of the dilemmas seem quite foreign as well. Though one of the novel’s tenets is that far more peope have had «things done» than will readily admit it, I can’t help but feel that this might be true of middle-class-and-up London, but I somehow doubt it is true of Trondheim. I’d be rather surprised, in fact, if any of my friends had had «things done» (at least more drastic than a bit of teeth bleaching or such). Perhaps I’m naive, but it does make the novel’s main existential discussion seem even less relevant.

So, yes, I liked it. I read it cover to cover much more quickly than I generally read things nowadays (what with life happening and all), and I will probably get hold of India Knight’s next book the moment it hits the shelves (as usual). And I half-way wish the next one will be about Clara and her familiy, too, because I’d like to know what happens next. But, no, I didn’t love it.

I may have to reread Comfort and Joy come Christmas, though.

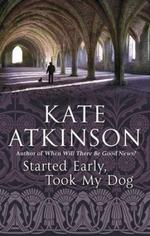

Having gotten my hands on Started Early, Took My Dog, I obviously had to start it as soon as possible.

Having gotten my hands on Started Early, Took My Dog, I obviously had to start it as soon as possible.